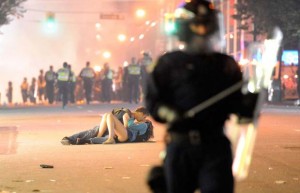

Richard Lam, 2011.

How can a cinematic image of “the masses” call a proletariat into being? There has to be a seductive element to an image; it must be “physiologically persuasive,” as Eisenstein et al. suggest in “Notes for a Film of ‘Capital'” (14).

There is something seductive about the image above; not just to me, but to people worldwide. I initially encountered Lam’s “kissing couple” in a Spanish newspaper and shortly thereafter saw it beneath Hebrew headlines during my semester of global learning. How a student at an American state university wound up at La Universitat de Valencia might be one part of the story behind how this became the image that repeatedly comes to mind when I try and imagine–literally, put an image to–neoliberal globalization.

I think that our reactions towards images can often be traced to desire. How is it that seeing a mass of people can help one imagine the possibility of a mass coalition? What role does desire play in translating this image of a mass to an actual mass movement? I think that both affect and desire need to be part of the conversation when we are thinking about the revolutionary potential of social media.

One place to look might be mimesis: how we seek to mimic the images we encounter. The image above both produces and calls upon a certain subjectivity, one rooted in romantic love amidst terror and violence. Both the fetishized female body and the whiteness of our protagonists–as compared to the black, anonymous, figure in the foreground–should not be overlooked. Something about this image seems universally understandable in today’s (well, 2011’s) historical moment. This image contains transnational allure. Looking to love amidst terror and violence has common currency in a world in which the 85 wealthiest people own as much as the poorest 50% of humanity.

In class we discussed the argument that film helped the masses to perceive themselves as such, making possible an understanding of the Russian Revolution as a rebellion of the proletariat. I’m interested in the way in which this image plays with our fantasies of what love looks like in such an unequal and violent world. Why, for instance, might more people recognize themselves in the fantasy of love pictured above, more so than here:

One circuitous detour that might (hopefully) lead us towards answers to these messy questions is through Jose Munoz’s description of the punk rock mosh pit in his article “Gimme Gimme This…Gimme Gimme That,” as a “destructive, generative, annihilative, and innovative” collision of people and objects (102). Munoz’s mosh pit speaks to projects involving the commons and what it feels like to be jostled by bodies in space. Punk rock/concert-loving fans may recognize this experience as desirable. Others, however, might be more desirous of the lover’s embrace, as captured in the first photo. *Perhaps it might be useful here to revisit the longer genealogy of crowd phenomenology, in the work of Engels and Benjamin.*

What, then, is to be done with these two images that suggest alternate styles of world-making amidst violence? If the first is an image of retreat into romantic love, the second is an opening up towards collective love. Part of what I’m struggling to do is take seriously the feeling of the first image in relation to the feeling of the second: the warmth, comfort, and security of a loving embrace and the jostled, unpredictable, and oftentimes invasive feelings of being in a crowd.

I maintain that we need to think about these desires and feelings, given the massive amounts of data that have been produced detailing worldwide inequality. How is it that this data has not produced material redistribution and greater social justice? Does new and better data (such as data visualizations) help draw us closer to social change?