*This blog is a work in progress that I intend to update*

It was only after visiting Kara Walker’s “A Subtlety,” on the subway ride home, that we realized how much more painful the sugar sculptures looked in digital photographs.

At the exhibit, I had to keep reminding myself that this is probably “supposed to” look like blood; these melting sugar sculptures are probably “supposed to” look like fire, and evoke scenes of violence. Looking back, though, I want to linger with my underlying assumption that good art needs to make us uncomfortable. I realize that before ever walking into the old sugar factory, I had already “read” the exhibit: it was going to reveal the geologically slow processes of history, layering the violence of slavery and sugar plantations into the present. Part of my experience was framed by this understanding, as I looked for “evidence” that would support it (the decline and dilapidation of the small brown children, the unblemished enormity of the white sphinx–the word “monolithic” kept coming to mind).

And this violent history was present, but so was a lot else. When you’re there–in the moment–the sweet scent is intoxicating and the lighting (in the late afternoon) is enchanting. It felt like being in an ambrosial cathedral. Like “A Subtlety,” cathedrals also invite reflections on violent histories, though they’re often visited for their beauty, rather than religious value. Both times I went, I had to consume something sweet afterwards. I couldn’t think about anything else until I sipped a mojito or ate gooey cake at Smorgasbord (going to Smorgasbord after “A Subtlety” deserves its own post). Both times I viscerally felt my body’s craving for sugar like an addict (and those of you who know me can attest to the reality of my sugar addiction). As an “homage,” it commemorates the lives of brown children that were the conditions of possibility for this craving. In trying to think through what the exhibit does rather than represents, it made me move towards sugar at an alarming rate.

In contrast to what I thought the exhibit ought to make me think about, the ambers emerging from these melting sugar children were so visually stunning that I couldn’t help remarking on their beauty, while simultaneously having ugly feelings about doing so. This fallen subtlety in particular contained shades of amber that I didn’t know could exist.

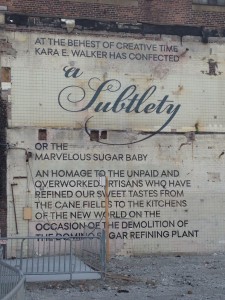

I think it is in the spirit of the exhibition to pay attention to its minor details, which are only minor–or subtle–from a privileged perspective, and to linger with the elements that are supposed to be background and peripheral, but are oftentimes the unseen infrastructures that silently perform. The first thing that struck me was the gorgeous, sweeping font used for the exhibit’s title, offset by the sans serif capital letters of the surrounding description. From the “y” tickling the “u” to the cleavage atop the “s,” the font is sensual and indulgent, like sugar once was and still both is (and is not).

Throughout the exhibit, you are invited to photograph it and tweet about it through the hashtag #karawalkerdomino. The result is that people milling throughout the warehouse alternate between viewing it from behind and beyond a lens–though let’s not forget the glasses and contact lenses that mediate most viewing experiences. Many of the photographs contain these spectators and their lenses, interpolating them into the exhibit itself. Especially surrounding the sphinx, viewers standing alongside her are placed at the level of the subtleties, inviting comparisons to their gorgeous, decaying bodies. For me, the exhibit raised more questions than it answered about the type of encounter–with art, with history–solicited through its invitation for digital participation. What, for instance, is at stake in sharing photographs of the exhibit? How do these invitations to share and participate relate to the complex histories crystallized in the sugar sculptures?

It’s commonplace to remark on how a photograph doesn’t do “justice” to the real thing. But in this case, and perhaps in all cases, the photographs reveal additional dimensions of the exhibit. Skirting discourses of justice and attendant assumptions of fairness, the photographs honor the exhibit by further complicating and proliferating its nuances/subtleties. In the photographs, the statues look like tar, like the pictures of blackened lungs used to scare children away from smoking. Each subtlety is surrounded by the slick of an oil spill.

The photographs foreground violence against bodies in a way that being there does not. Unlike being in the space, where I had to keep reminding myself that these incredible statues commemorate violent histories, there is no honeyed aura surrounding the photographs. These photographs are simulacra: reproductions for which there is no original. Morphing from one moment to the next, “A Subtlety” illustrates the thermodynamics of social change, how violence against African Americans has not disappeared, but transmuted into new forms.

The dissolving ballerina gracefully arches towards the sticky light refracted in her future. Although the syrupy sweetness of the exhibit will disappear when the factory is demolished, these pictures will live on. As will the sap on the treads of our shoes.

Here, I’ve provided only my own photographs, though many others are available through Twitter.

Some things I want to continue thinking about (and would love to hear others’ thoughts on!):

- How the exhibit relates to technology and collaboration. Although it “belongs” to Kara Walker, it was made possible by massively collaborative efforts and advanced computer technologies. In addition, the exhibit seems to expand as it implicates contributors through digital mutations.